英国禁止圣诞颂歌的那段历史

编辑:给力英语新闻 更新:2017年12月5日 作者:克莱门西·伯顿-希尔(Clemency Burton-Hill)

说到革命中表达反抗的歌曲,你会想到什么?是比莉·荷莉戴(Billie Holliday)的《奇异果》(Strange Fruit)?鲍勃·迪伦(Bob Dylan)的《在风中飘荡》(Blowin’ In The Wind)?还是山姆·库克(Sam Cooke)的《变革将至》(A Change is Gonna Come)?我猜卑微的圣诞颂歌的排名大概不会靠前。

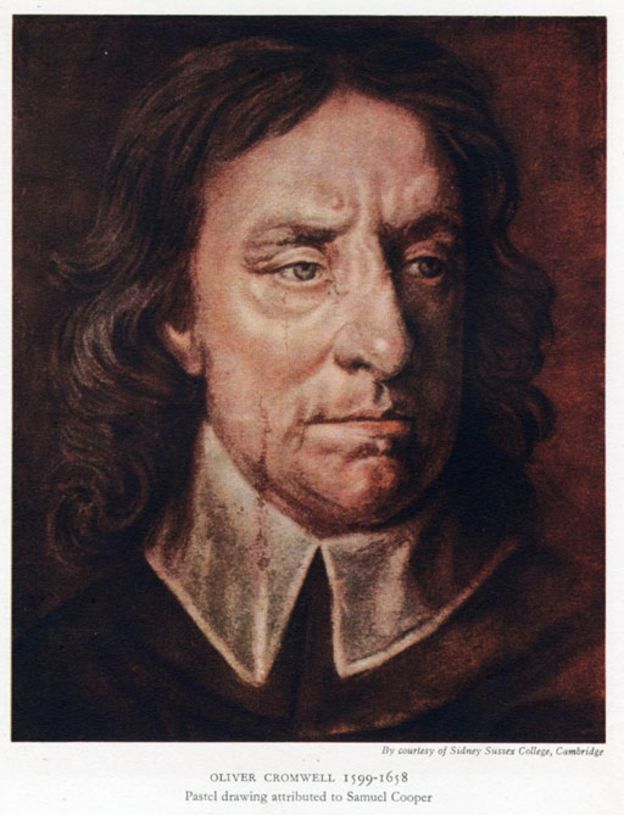

但是在17世纪中期,在英国内战期间,唱The Holly and the Ivy这样的圣诞节歌曲可能会给你带来大麻烦。当时的议会军领袖奥利弗·克伦威尔(Oliver Cromwell)(后来他成为英格兰、苏格兰和爱尔兰联邦的护国公)以整顿该国的颓废文化为己任。圣诞节和所有的节日装饰首当其冲。

从中世纪至今,圣诞节的庆祝方式基本没有变化:12月25日是纪念耶稣降生的神圣日子,这一天开始,直至1月5日的第十二夜(Twelfth Night),节日的快乐气氛一直持续。教堂举行特殊的礼拜,商店的营业时间缩短,人们用冬青树、常春藤和槲寄生装饰自己的家,剧团会表演喜剧(它是现代哑剧的雏形),酒馆里人们纵欲狂欢,亲友团聚享受节日的特别饮食,比如火鸡、圣诞甜果派、乌梅粥和圣诞特别酿制的麦芽酒,大街小巷都唱着圣诞歌曲。

圣诞颂歌数千年前已在欧洲出现,“颂歌”这个词可能来自法语词“carole”,意思是配乐舞蹈。它们最初是用在异教徒冬至日等活动时。后来,早期的基督教徒借用了这一形式:公元129年,罗马主教敕令在罗马的圣诞礼拜中演唱一首名为Angel’s Hymn的颂歌。

奥利弗·克伦威尔从1653年至1658年去世前一直担任英国的护国主

到中世纪,圣诞节的十二天里,“祝酒者”会挨家挨户去唱歌,他们有几百首以耶稣降生为主题,以冬青树、常春藤作比的英语颂歌。连亨利八世(1491-1547)也写了一首名为Green Groweth the Holly的颂歌,这首歌的精美手稿现藏于大英图书馆(the British Library)。

“圣诞颂歌”这个表达出现在早期的拉丁语-英语词典中,17世纪的著名抒情诗人罗伯特·赫里克(Robert Herrick)在一首颂歌的开头这样写道:“还有比这更甜美的歌谣吗?”亨利·劳斯(Henry Lawes)的原作配乐很遗憾已经失传,但是约翰·拉特(John Rutter)为这首诗编排了现代的曲调,让它在圣诞节颇受欢迎,这展现了传统的颂歌写作强大的生命力。

对克伦威尔和他的清教徒伙伴来说,圣诞颂歌和其他圣诞节活动不止让人厌恶,更是一种罪恶。根据史料记载,他们认为在12月25日庆祝耶稣的生日带有罗马天主教的色彩,是一种来自罗马天主教铺张浪费的传统,而且没有得到圣经的支持,它会威胁到基督教的核心信仰。他们认为,上帝从未号召人类以这种方式来庆祝耶稣降生。1644年,议会的一项法案禁止了这一节日,1647年,长期议会(Long Parliament)通过了一项条例,确定废除了圣诞节的晚宴。

“管它呢”

但是英国男女老少对节日的热情和呼声并未因此而消减。圣诞禁令下达后的近二十年里,每年12月25日,人们还是会偷偷摸摸举行纪念耶稣降生的宗教仪式,并且继续偷偷唱圣诞歌。圣诞颂歌基本上进入了地下状态——不过一些反叛者仍决心坚持大唱颂歌。

1656年12月25日,众议院的一名议员抱怨前一天晚上邻居“为这个愚蠢的日子作准备”而制造的噪音让他一夜未眠。随着1660年英国王室复辟,从1642至1660年之间的立法全部作废,于是圣诞节十二天的宗教活动和世俗活动终于重获自由。

不仅自古以来广为传唱的圣诞颂歌骄傲地幸存了下来,人们还对颂歌燃起了新的热情:18世纪和维多利亚时代是颂歌写作的黄金时代,不少为现代人所喜爱的名曲正是出自那个时代——包括O Come All Ye Faithful 和 God Rest Ye, Merry Gentlemen。

BBC每年都会录制并向全世界播放剑桥大学国王学院每年一次的盛事——九篇读经与圣诞颂歌庆典(A Festival of Nine Lessons and Carols)

那么,为什么人们要冒险继续唱颂歌呢?毕竟古典音乐界的“纯粹主义者”可能会认为它是一种较低级的艺术形式,在他们眼里媚俗音乐当然不会是“真正的”音乐艺术。但这只是一种文化势利眼。艺术界的一些顶级作曲家,包括费利克斯·门德尔松·巴托尔迪(Felix Mendelssohn)和古斯塔夫·霍尔斯特(Gustav Holst)在内,已经开始创作圣诞颂歌(Hark! The Herald Angels Sing 和 In The Bleak Midwinter)。

颂歌既可以感人至深,也可以包含许多复杂的音乐概念,尽管它们的规模比不上管弦交响乐。这些经过时间沉淀的瑰宝通过电影配乐的形式让大众有机会接触到古典音乐,而人们常常以为必须要先获得音乐学位才可以获准进入古典音乐的殿堂。

那么,为什么圣诞颂歌有那么大的力量?剑桥大学克莱尔学院(Clare College)的音乐指挥家格雷厄姆·罗斯(Graham Ross)所带领的合唱团在节日期间颇受欢迎。他们的圣诞音乐新专辑 Lux de Caelo 探索了传统作品和一些鲜为人知的作品。他指出圣诞节是人们通过音乐重新建立联系的良机。“圣诞颂歌让人们走到一起。

一年中很少有这样的时候,人们放下手上的事情,聚在一起,唱歌过节。合唱著名颂歌在不同的文化和语言之间建立了直接的联系,人们放下各自的政治背景,一起享受纯粹的快乐。现在,人们很少有机会做这样的事。”

确实,对世界上的很多人来说,圣诞季通常是他们聆听非流行音乐的唯一固定机会。圣诞节被禁的历史已经过去近四百年了,但是每年的这个时候,人们仍然会欢聚一堂,一起唱歌。

When Christmas carols were banned

When it comes to revolutionary protest songs, what springs to mind? Billie Holliday’s Strange Fruit? Bob Dylan’s Blowin’ In The Wind? Sam Cooke’s A Change is Gonna Come? I’m guessing the humble Christmas carol is probably low on your list of contenders, but in mid-17thCentury England, during the English Civil War, the singing of such things as The Holly and the Ivy would have landed you in serious trouble. Oliver Cromwell, the statesman responsible for leading the parliamentary army (and later Lord Protector of England, Scotland and Ireland), was on a mission to cleanse the nation of its most decadent excesses. On the top of the list was Christmas and all its festive trappings.

Since the Middle Ages, Christmas had been celebrated in much the same way as today: 25 December was the high holy day on which the birth of Christ was commemorated, and it kicked off an extended period of merriment, lasting until Twelfth Night on 5 January. Churches held special services; businesses kept shorter hours; people decorated their homes with holly, ivy and mistletoe; acting troupes put on comedic stage plays (prefiguring the modern pantomime); taverns and taphouses were brimming with merrymakers; and families and friends came together to gorge themselves on special food and drink including turkey, mince pies, plum porridge and specially-brewed Christmas ale. And communal singing about the season was all the rage.

The first ‘carols’ had been heard in Europe thousands of years before, the word probably deriving from the French carole, a dance accompanied by singing. These tended to be pagan songs for events such as the Winter Solstice, until the early Christians appropriated them: a Roman bishop in AD 129, for example, decreed that a carol called Angel’s Hymn be sung at a Christmas service in Rome. By the Middle Ages, groups of ‘wassailers’, who went from house to house singing during the Twelve Days of Christmas, had at their disposal many hundreds of English carols featuring nativity themes and festive tropes such as holly and ivy. Even King Henry VIII (1491-1547) wrote a carol called Green Groweth the Holly, whose beautiful manuscript can be seen in the British Library. The phrase ‘Christmas caroll’ is mentioned in an early Latin-English dictionary, and one of the great lyric 17th Century poets, Robert Herrick, wrote a carol text beginning: “What sweeter music can we bring?” The original music by Henry Lawes is sadly lost, but a contemporary setting of the poem by John Rutter is a modern seasonal favourite, proving just how evergreen the tradition of carol-writing is.

Green Groweth the Holly - written by King Henry VIII

To Cromwell and his fellow Puritans, though, singing and related Christmas festivities were not only abhorrent but sinful. According to historical sources, they viewed the celebration of Christ’s birth on 25 December as a “popish” and wasteful tradition that derived – with no biblical justification – from the Roman Catholic Church (‘Christ’s Mass’), thus threatening their core Christian beliefs. Nowhere, they argued, had God called upon mankind to celebrate Christ’s nativity in such fashion. In 1644, an Act of Parliament effectively banned the festival and in June 1647, the Long Parliament passed an ordinance confirming the abolition of the feast of Christmas.

Bah humbug

But the voices and festive spirits of English men, women and children were not to be so easily silenced. For the nearly two decades that the ban on Christmas was in place, semi-clandestine religious services marking Christ’s nativity continued to be held on 25 December, and people continued to sing in secret. Christmas carols essentially went underground – although some of those rebellious types determined to keep carols alive did so more loudly than others. On 25 December 1656, a a member of parliament in the House of Commons made clear his anger at getting little sleep the previous night because of the noise of their neighbours’ “preparations for this foolish day…” Come the Restoration of the English monarchy in 1660, when legislation between 1642-60 was declared null and void, both the religious and the secular elements of the Twelve Days of Christmas were allowed to be celebrated freely. And not only had the popular Christmas carols of previous eras survived triumphant but interest in them was renewed with passion and exuberance: both the 18th Century and Victorian periods were golden eras in carol-writing, producing many of the treasures that we know and love today – including O Come All Ye Faithful and God Rest Ye, Merry Gentlemen.

So why did people continue to sing carols, against the odds and with such high stakes? After all, many ‘purists’ in the classical world might argue that they are a rather lowly art form – musical kitsch, certainly not ‘real’ music. But this is mere cultural snobbery. Some of the greatest composers in the canon, including Felix Mendelssohn and Gustav Holst, have turned their hand to writing Christmas carols (Hark! The Herald Angels Sing and In The Bleak Midwinter, respectively.) Carols can be deeply touching and affecting, containing plenty of complex musical ideas even if they lack the scale of an orchestral symphony. Distilled little gems, they share a quality with film soundtracks, being another wonderful way into classical music for people who might otherwise be scared off by the idea they need a degree in musicology before they are ‘allowed’ to listen to classical music.

So why are Christmas carols so powerful? Graham Ross is Director of Music at Clare College, Cambridge, whose outstanding choir is always much in demand during the festive season, and whose superb new album of Christmas music, Lux de Caelo explores both traditional and lesser-known works. He points out that Christmas offers a golden opportunity to reconnect through music. “A Christmas carol brings people together. It's one of the few times in the year that people stop what they're doing, spend time with one another, and sing together to celebrate. Communal singing of well-known carols offers an immediate connection across cultures and languages, putting aside any political backgrounds and bringing together a group of people for sheer enjoyment. Nowadays, there aren't many things that can do that.’

Indeed, for many people around the world, the festive season is often the only time they regularly hear music of a non-pop variety. Today, almost four centuries after they were banned, people will still, inevitably, gather joyfully to sing at this time of the year.