圣诞馅饼:一段传奇未知的历史

编辑:给力英语新闻 更新:2017年12月24日 作者:维洛妮可·格林伍德(Veronique Greenwood)

值此圣诞佳节到来之际,含酒精的百果馅饼无疑将出现在家家户户的餐桌上,提振你的心情,再让你的臀围大上一圈。这道甜点虽然个头小,但却无处不在,以至于很容易使得人们不把它当回事。不过,实际上,圣诞馅饼的历史由来已久,它们可是从笨重的羊肉馅面饼逐渐被改良为今天这种小巧馅饼的。

围绕着圣诞馅饼还曾出现过不少引人入胜、经久不衰的传说故事,不过这大概更多地反映了人们的偏见,以及一个事实:好故事的吸引力比这道甜点本身的吸引力要大。

很久以前,人们就发明了馅饼这道美味佳肴。一开始,制作馅饼的原材料里并没有黄油和起酥皮。在几个世纪里,馅饼皮的原材料都是面粉团和裹着馅料、在烘焙过程中能保持水分的水面团。

《馅饼的历史》(Pie: A History)一书的作者詹妮特·克拉克森(Janet Clarkson)表示,人们做那些厚达几英寸的馅饼盒,可能并不是为了食用。直到人们开始往面团里添加脂肪,馅饼才逐渐接近今天的样子,不过那时的馅饼皮依旧像极了某种原始的保鲜容器。

一个烘焙得当的馅饼——液体脂肪流入面团撑开的空隙中——甚至可以保存一整年,馅饼皮能够阻挡空气的侵入和馅饼的腐烂。虽然今天的我们很难理解这一情形,但是克拉克森表示:"我们可以推测,人们曾经通过这样的方法保存食物。"

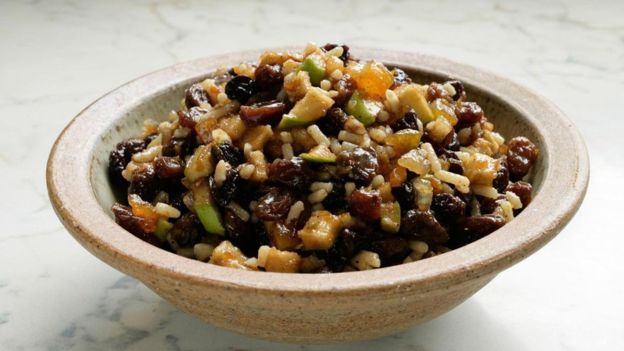

早期的馅饼比今天的要大得多,有甜味也有咸味(图片来源: Alamy)

Early mince pies were much bigger than modern treats - and had a sweet and savoury meat-based filling (Credit: Alamy)

在1390年以卷轴形式出现的英文菜谱《烹饪的方法》(A Forme of Cury)中,有一道需要大量香料和肉制作的菜,叫作"肉馅饼"。为了制作这道菜,厨师们需要按照制作方法,擀压猪肉、煮得过熟的鸡蛋,以及奶酪,再将擀压好的馅料与香料、藏红花及砂糖混合。

其他能够令人联想到今天的圣诞馅饼的食谱包括了出现在哲瓦斯·马克汉姆(Gervase Markham)1615年出版的书《英国女管家》(The English Huswife)中的菜谱。该菜谱需要的原材料包括一整只羊腿、三磅板油,以及盐、四叶草、肉豆蔻干皮、小葡萄干、葡萄干、李子、枣、橘子皮。用这一菜谱做出的馅饼大而结实——它们可不是用两只手捏起来吃的,其尺寸大到一次可供多人食用。

17世纪中叶,虽然人们也在其他时候吃这种馅饼,但它逐渐开始与圣诞节产生联系。塞缪尔·皮普斯(Samuel Pepys)在1661年1月一位朋友的婚礼周年派对上品尝了肉馅饼,当时一共呈上了18个肉馅饼,每一个代表了一年的婚姻生活。似乎塞缪尔也期待着在圣诞节的时候品尝到它们。有一年,因为妻子病得无法亲自下厨房,塞缪尔甚至请人送来了肉馅饼。

然而,今天仍流传着那个时代关于肉馅饼的传说,实际上还要再早一点点,在奥利弗·克伦威尔(Oliver Cromwell)统治英国期间。在这一君主制空白期,掌权的清教徒大力清除他们眼中基督教信仰里轻浮且对神不敬的内容,甚至试图废除圣诞节等宗教节日。虽然废除圣诞节的法案并未在议会通过,但另一个要求圣诞节期间市场必须正常开放,以及圣诞节当天教堂礼拜活动不得与往常有所不同的法案得以通过。其他法律还野蛮地打击了宗教节日期间各种形式的庆祝大餐和仪式。

在奥利弗·克伦威尔的统治下,节庆盛宴被大力压制——但他唯独没有禁止人们制作圣诞馅饼(图片来源: Alamy)

Oliver Cromwell's reign saw a crackdown on festive feasts - but he didn't ban mince pies (Credit: Alamy)

各种法律条文中并未特意提及馅饼。不过在后来的许多年里,有关克伦威尔统治期间的传言是,这道深受天主教宠爱的食品当时被认定是非法食品。在1661年出版的一本有关君主制空白期的书里,作者提到了这样的文字:

"所有李子都是对先知子孙的蔑视"香料汤太热辣"十二月的馅饼里有叛国罪"锅子里装着死亡。"

1850年,小说家华盛顿·欧文(Washington Irving)如此写道:"距离可怜的馅饼在全国范围内遭受惨烈迫害,以及李子粥被认为是对教会制度的亵渎已经过去了近200年。"即使在今天,圣诞期间,我们也能在报纸上读到类似的说法:"明天,当你开始往圣诞馅饼里塞馅料之前,请注意,其实你正在触犯法律。"某篇文章如此坚称。此类说法往往错误地认为克伦威尔统治期间制定的法律从未被废止。这些说法只不过是一系列猜想引起的杜撰,一块馅饼居然能和政治产生联系,这样的想法对人们很有吸引力。

如果你对圣诞馅饼实际上完全合法这一事实感到失望,那么这里还有一个小八卦:根据《芝加哥读者报》(Chicago Reader)里曾刊登过的一篇有趣的故事,在禁酒令时期的芝加哥,罐装圣诞馅饼馅料里的酒精含量达14%以上之高。这足以让人们充分感受到圣诞气氛了。

圣诞馅饼最重要的也许就是其馅料从肉馅到甜馅的转变,1747年汉娜·哥拉瑟(Hannah Glasse)完成了她的《烹饪艺术》(Art of Cookery)一书。她首次指导读者们将小葡萄干、葡萄干、苹果、砂糖和板油的混合物铺在派皮里,加入柠檬、橘子皮和红酒进行烘焙。她这样表示:"如果你想要给馅饼里加入肉馅,请将一只牛舌煮到半熟,去皮,尽可能切得细腻,并与其他馅料混合。" 尽管该菜谱的表述有些模糊——在上下文中读者能够读出将肉与甜馅料混合的意思——但它确实给出了不加肉、纯甜馅的选择。

从18世纪起,今天这种添加香料和甜果馅的圣诞馅饼越来越流行(图片来源: Alamy)

The modern, sweet-and-spicy mixture became more popular from the 18th Century (Credit: Alamy)

得益于西印度群岛甘蔗园的兴盛,砂糖越来越便宜且容易入手,甜馅饼也越来越普遍。1861年,毕顿女士(Mrs Beeton)的书《家庭管理》(Household Management)向大家展示了除肉馅以外,另一种不以肉为馅料的甜馅饼的做法。到了维多利亚时代,圣诞馅饼已经完完全全被划入甜食阵营。

在圣诞馅饼的演变历史中唯一不变的是:制作圣诞馅饼过程复杂。塞缪尔·皮普斯曾这么描写自己独自前去参加圣诞礼拜的经历:"我那被留在家里的妻子,尽管已经困得不行,还是撑到凌晨四点,以确保佣人做好圣诞馅饼。"

The strange and twisted history of mince pies

Fruity, boozy little mouthfuls, mince pies will doubtless make an appearance on every table this holiday season, making spirits bright and then going straight to your hips. The diminutive treats are so omnipresent it's easy to take them for granted, but they have a long history, which saw them morph from hefty ground-mutton goodies into today's dainty tarts.

They've even been caught up in some intriguing, longstanding legends, which reveal perhaps more about people's prejudices and desire for a good story than about the dessert itself.

Pies as a culinary art form are old inventions, although they haven't always involved buttery, flaky pastry. For many centuries, they seem to have been primarily shells of flour and water paste wrapped around a filling to keep it moist while baking.

The cases, which could be several inches thick, according to Janet Clarkson, author of Pie: A History, were perhaps not even intended to be edible. Even once fat had begun to be added to the dough, bringing us into the realm of modern pastry, a pie crust was still sometimes considered more as a kind of primitive Tupperware.

A well-baked meat pie, with liquid fat poured into any steam holes left open and left to solidify, might even be kept for up to a year, with the crust apparently keeping out air and spoilage. It seems difficult to fathom today, but as Clarkson reflects, “it was such a common practice that we have to assume that most of the time consumers survived the experience”.

A pie full of spices and meat appears in 1390 in A Forme of Cury, an English cookbook originally written on a scroll, under the name “tartes of flesh”. To make these morsels, cooks were instructed to grind up pork, hard-boiled eggs, and cheese, before mixing them with spices, saffron, and sugar.

Other recipes redolent of today's mince pies include one that appears in Gervase Markham's The English Huswife, published in 1615. In this recipe, an entire leg of mutton and three pounds of suet go in, along with salt, cloves, mace, currants, raisins, prunes, dates, and orange peel. They were big, sturdy things – these pies were not finger food, but enough to serve many diners at once.

Stories began to circulate that during Cromwell's reign, the spiced treats, derided as a Popeish indulgence, had been made illegal

By the mid-17th Century, there appears to have been some connection made to Christmas, although people certainly ate mince pies at other times as well – Samuel Pepys had mince pies at a friend's anniversary party in January of 1661, where there were 18 laid out, one for each year of the marriage. But he also appears to have expected them for Christmas. When his wife was too ill to make them one year, he had them delivered.

However, a hint of scandal today swirls around mince pies during this period – or rather, just before it, during Oliver Cromwell's reign over England. During this Interregnum, when the Puritans were in power, they came down hard on what they saw as frivolous, godless additions to the Christian faith, going so far as to try to abolish holy days, including Christmas. While that particular bill did not pass Parliament, another one did, mandating that markets should stay open on Christmas and legislating that nothing in church services should be out of the ordinary that day. Other laws cracked down brutally on holy day feasting and ceremonies of all kinds.

There was no mention of mince pies in particular. But in later years, stories began to circulate that during Cromwell's reign, the spiced treats, derided as a Popeish indulgence, had been made illegal. In a 1661 book about the Interregnum, the author mentions the following rhyme:

“All Plums the Prophet's sons defy

“And Spice-broths are too hot

“Treason's in a December-pye

“And death within the pot.”

Novelist Washington Irving wrote in 1850, “nearly two centuries had elapsed since the fiery persecution of poor mince pie throughout the land, when plum porridge was denounced as mere popery”. Even today, you can find the idea in newspapers around Christmas, often with the added misconception that laws made during Cromwell's reign were never repealed. “Before you start tucking into a mince pie tomorrow – beware as you're actually breaking the law,” insists one article. These tales, however, are just myths arising from a series of assumptions and the attractiveness of the idea that pastry could be political.

Canned mince pie filling during Prohibition-era Chicago saw its alcohol levels spike to more than 14%

If you are disappointed that mince pies are, in fact, perfectly licit, here's another scandalous tidbit: according to a lovely essay in the Chicago Reader, canned mince pie filling during Prohibition-era Chicago saw its alcohol levels spike to more than 14%. That's quite enough to have made people very merry indeed.

Perhaps a more important change in mince pies has been the transition from meat to sweet, which it appears was already underway by the time Hannah Glasse wrote her Art of Cookery in 1747. She first directs the reader to blend currants, raisins, apples, sugar, and suet, which should be layered in pastry crust with lemon, orange peel and red wine before being baked. She then adds, “If you chuse[sic] meat in your pies parboil a neat’s tongue, peel it, and chop the meat as fine as possible and mix with the rest.” While the recipe is a bit ambiguous – in context it's possible to read it as expecting meat to be layered in with the sweet mince – this does suggest the option of just a sweet tart, no meat required.

As sugar became cheaper and easier to get, thanks to the rise of sugarcane plantations in the West Indies, sweet pies seem to have grown more common. In 1861, Mrs Beeton's Book of Household Managementgave instructions for a meat-free sweet version alongside a meaty one. And by the Victorian era mince pies were firmly in the sugary camp.

One constant throughout this period of recipe flux, however, remained: making mince pies has always been a lot of work. Samuel Pepys wrote one year that he went to the Christmas service alone, “leaving my wife desirous to sleep, having sat up till four this morning seeing her mayds make mince-pies.”