信或不信神,圣诞都与你同在

编辑:给力英语新闻 更新:2017年12月4日 作者:T·M·鲁尔曼(By T. M. LUHRMANN)

这个圣诞节我们全家会去教堂。那是一座美丽的老教堂,在迷人的新罕布什尔小镇沃尔浦尔,离佛蒙特州界不远。圣坛后的墙上悬挂着主祷文。读经台耸立在中殿前,让高高在上的牧师可以俯瞰他的教众。长椅和侧席有种严肃、纯粹的特质,这和曾经来教堂面对上帝的殖民地公理会教众是相称的。

不过这是个一位论派教堂。一位论派始于近代欧洲,当时的一些人拒绝接受三位一体的神论,信奉上帝只有一位的教义。到了19世纪,一位论派已经成为一些知识分子的聚集地,这些人对信仰的主张产生了质疑,但同时又希望能以某种方式保持信念。例如在日渐加剧的疑惑中挣扎着的查尔斯·达尔文(Charles Darwin),就选择了一位论。我的母亲是一位浸礼会牧师的女儿,从神学的角度来说,她是家中的“黑羊”。她愿意去教堂,但不太确定是否需要上帝。现代一神普救派协会(Unitarian Universalist Association)的准则宣言中,完全没有提到上帝。

事实上这种无神的信仰正在迅速兴起,在很多地方,上帝的戏份要比一位论中还要少。无神论者的宗教仪式在全美各地出现,包括在“圣经地带”(Bible Belt)。

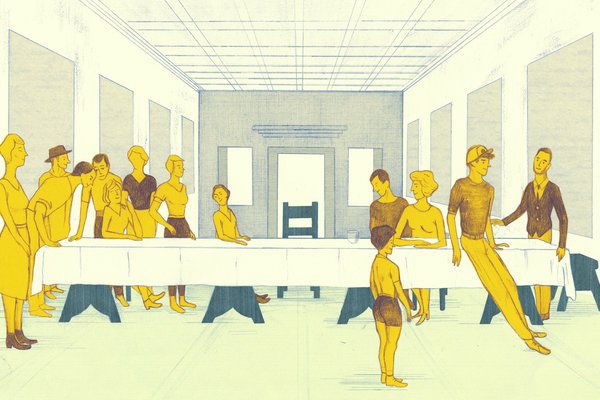

其中相当一部分跟“礼拜日大会”(Sunday Assembly)有关,这是一个由英国谐星桑德森·琼斯(Sanderson Jones)和皮葩·伊文斯(Pippa Evans)创办的集会。他们是公开的无神论者。然而他们开创的这个运动,吸引了成千上万的人前来参加,活动包含有音乐、讲道、诵读、反思等内容,甚至(从照片上看)还会挥动高举的双手。全球有将近200个礼拜日大会的举办地。去年在洛杉矶的一次集会吸引了数百名参与者。

对信仰心存犹豫,甚至已经没有信仰,却还渴望举办一种“礼拜”仪式,我们该如何理解这样的一种冲动呢?对社群的追求无疑是一部分原因。琼斯在接受美联社(The Associated Press)采访时就这样说:“唱好听的歌,听有趣的讲话,思考如何提高自己,帮助他人——在一个关系融洽的社群中做这些事。这样的事,哪点你不喜欢?”

还有一个原因是,仪式会改变我们对注意力的投放,这和它作为一种信仰表达方式是同等重要的——甚至可能更重要。在《仪式之原型行为》(The Archetypal Actions of Ritual)一书中,人类学家卡洛琳·亨弗莱(Caroline Humphrey)和詹姆斯·雷德洛(James Laidlaw)甚至直陈仪式和抒发宗教信念毫无关系,它的重点是以一种和日常生活不同的方式去做某事,迫使你觉得这事很重要。他们认为,通过举行一场仪式来让你把注意力集中于某个瞬间,让你对这个瞬间顿生崇敬之情。

在英国,无神论者的比例远高于美国,各种组织应运而生,伴那些认为自己没有信仰的人走过人生各个阶段。人类学家马修·恩格尔克(Matthew Engelke)在2011年花了很多时间和英国人道主义协会(British Humanist Association)共事,那是该国非常知名的非宗教组织,拥有超过1.2万名成员。著名的无神论人士、演化生物学家理查德·道金斯(Richard Dawkins)就是其中之一。该协会资助了许多反宗教政治活动。他们希望政府停止向有宗教背景的学校拨款,剥夺圣公会主教在上议院的席位。他们还会主持葬礼、婚礼和命名礼。2011年,该协会成员举行了9000场这样的仪式。不管对象的神学观是什么,这些典礼是有意义的。

更重要的是,这些仪式有效果,这里的“效果”意思是说它改变了人们对生活的感受。原来,说出你的感恩,会让你心生感恩。说出你的欣喜,会让你感到欣喜。我们都知道在这个世界上语言是多么靠不住,因此这些话会显得奇怪。但这是真实的。

有一项研究要求本科生每周写一篇文章,讲述让自己感激或欣喜的事;烦心的事;或“过去一周里打动了你的事件或境遇”,那些叙述了感激之情的人,对自己人生的看法会有总体上的改善,会更乐观地看待接下来的一周。类似的研究现在有很多。

从根本上说,宗教是一种帮助人们去看清世界真实面貌的办法,但又要在某些方面、某种程度上,帮助人们按照它最理想的形态去体验它。人们在教堂里做的很多事——寻找友爱,庆祝新生与结合,缅怀逝者,重申我们珍视的价值观——即便抱着上帝只是一种隐喻或故事的想法,也是可以去做的,甚至可以完全不提及神。

然而没有神的宗教也许更令人神伤。无神论者相信人际关系,不信超自然的关系,而说到实现一个理想世界,人类是不太擅长的。也许这就是为什么我们会被圣诞颂歌所打动,因为它们呼唤的是一个能实现的世界,而不是我们所知的世界。

愿圣诞之精神与你们同在,无论你怎么理解这句话的含义。

T·M·鲁尔曼是观点文章作者、斯坦福大学人类学教授。

翻译:经雷

Religion Without God

This Christmas our family will go to church. The service is held in a beautiful old church in the charming town of Walpole, N.H., just over the border from Vermont. The Lord’s Prayer hangs on the wall behind the sanctuary. A lectern rises above the nave to let the pastor look down on his flock. The pews and the side stalls have the stern, pure lineaments suited to the Colonial congregation that once came to church to face God.

Except that this church is Unitarian. Unitarianism emerged in early modern Europe from those who rejected a Trinitarian theology in preference for the doctrine that God was one. By the 19th century, however, the Unitarian church had become a place for intellectuals who were skeptical of belief claims but who wanted to hang on to faith in some manner. Charles Darwin, for example, turned to Unitarians as he struggled with his growing doubt. My mother is the daughter of a Baptist pastor and the black sheep, theologically speaking, of her family. She wants to go to church, but she is not quite sure whether she wants God. The modern Unitarian Universalist Association’s statement of principles does not mention God at all.

As it happens, this kind of God-neutral faith is growing rapidly, in many cases with even less role for God than among Unitarians. Atheist services have sprung up around the country, even in the Bible Belt.

Many of them are connected to Sunday Assembly, which was founded in Britain by two comedians, Sanderson Jones and Pippa Evans. They are avowed atheists. Yet they have created a movement that draws thousands of people to events with music, sermons, readings, reflections and (to judge by photos) even the waving of upraised hands. There are nearly 200 Sunday Assembly gatherings worldwide. A gathering in Los Angeles last year attracted hundreds of participants.

How do we understand this impulse to hold a “church” service despite a hesitant or even nonexistent faith? Part of the answer is surely the quest for community. That’s what Mr. Jones told The Associated Press: “Singing awesome songs, hearing interesting talks, thinking about improving yourself and helping other people — and doing that in a community with wonderful relationships. Which part of that is not to like?”

Another part of the answer is that rituals change the way we pay attention as much as — perhaps more than — they express belief. In “The Archetypal Actions of Ritual,” two anthropologists, Caroline Humphrey and James Laidlaw, go so far as to argue that ritual isn’t about expressing religious commitment at all, but about doing something in a way that marks the moment as different from the everyday and forces you to see it as important. Their point is that performing a ritual focuses your attention on some moment and deems it worthy of respect.

In Britain, where the rate of atheism is much higher than in the United States, organizations have now sprung up to mark life passages for those who consider themselves to be nonbelievers. The anthropologist Matthew Engelke spent much of 2011 with the British Humanist Association, the country’s pre-eminent nonreligious organization, with a membership of over 12,000. The evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins, a prominent atheist, is a member. The association sponsors a good deal of anti-religious political activity. They want to stop faith-based schools from receiving state funding and to remove the rights of Church of England bishops to sit in the House of Lords. They also perform funerals, weddings and namings. In 2011, members conducted 9,000 of these rituals. Ceremony does something for people independent of their theological views.

Moreover, these rituals work, if by “work” we mean that they change people’s sense of their lives. It turns out that saying that you are grateful makes you feel grateful. Saying that you are thankful makes you feel thankful. To a world so familiar with the general unreliability of language, that may seem strange. But it is true.

In a study in which undergraduates were assigned to write weekly either about things they were grateful or thankful for; hassles; or “events or circumstances that affected you in the past week,” those who wrote about gratitude felt better about their lives as a whole, and were more optimistic about the coming week. There have now been many such studies.

Religion is fundamentally a practice that helps people to look at the world as it is and yet to experience it — to some extent, in some way — as it should be. Much of what people actually do in church — finding fellowship, celebrating birth and marriage, remembering those we have lost, affirming the values we cherish — can be accomplished with a sense of God as metaphor, as story, or even without any mention of God at all.

Yet religion without God may be more poignant. Atheists trust in human relations, not supernatural ones, and humans are not so good at delivering the world as it should be. Perhaps that is why we are moved by Christmas carols, which conjure up the world as it can be and not the world we know.

May the spirit of Christmas be with you, however you understand what that means.

T. M. Luhrmann, a contributing opinion writer, is a professor of anthropology at Stanford University.