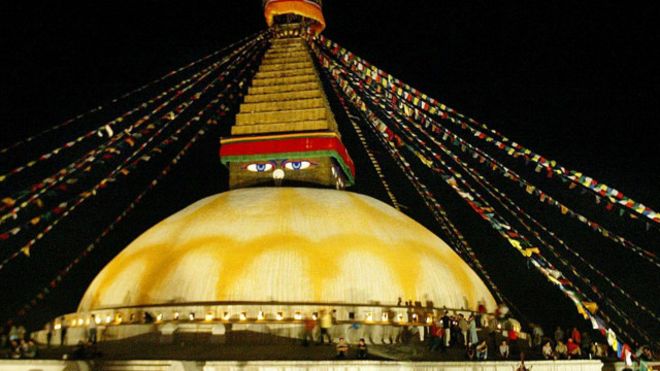

佛陀诞生地——蓝毗尼 - BBC苏丝米塔·巴拉尔(Susmita Baral)(2023年7月29日)

蓝毗尼(Lumbini)有全世界最大的佛舍利塔之一。这是在佛陀生日那天的照片。(图片来源:Paula Bronstein/Getty)

从印度到韩国,在亚洲各地遍布着成千上万座寺庙、寺院、舍利塔和佛塔,它们是拜佛的场所,也是佛教戒律的象征。

但是,蓝毗尼的象征意义和历史价值是所有这些佛教建筑都无法望其项背的。蓝毗尼是喜马拉雅山脚下尼泊尔南部特莱平原(Terai)的一个专区。公元前623年,净饭王(King Suddhodhana)和王后摩诃摩耶(Maya Devi)在蓝毗尼生下乔达摩·悉达多王子(Siddhartha Guatama)。蓝毗尼因此成为全世界4.88亿佛教徒前去朝圣的四大圣地之一。

蓝毗尼于1997年被评定为世界遗产, 数百年来它吸引了无数的游客和朝圣的佛教徒。公元前249年,印度阿育王(Ashoka)到这里参访,建起4座舍利塔和一座以马为柱头的石柱,以表达他的崇敬之情。这里一度沉寂,不过1896年,德国考古学家阿洛伊斯·安东·福特勒(Alois Anton Führer)又重新发现了这个地方。根据对遗迹的考古分析,后来这里被认定为佛陀的诞生地。

尼泊尔的佛教徒在蓝毗尼的摩耶夫人祠(Maya Devi Temple)祝祷(祈祷)(图片来源:PrakashMathema/AFP/Getty)

现在,每年有40多万游客来探访这个圣地。他们在古代寺院和舍利塔的遗迹里游览,按顺时针方向绕着阿育王的舍利塔和石柱致敬。他们参观摩耶夫人祠,据说王后就是在附近的一个池塘沐浴后在这里分娩。每年4月或5月,在第一个满月吠舍佉月(Vaisakh),当为期一天的佛诞日来临时,成千上万的人来到这个地方祝祷、冥想,以纪念佛陀的诞生、顿悟和涅槃。

蓝毗尼不仅是一个佛教圣地,也吸引着成千上万不同背景和不同宗教信仰的人来到这里,类似于梵蒂冈的圣彼得大教堂(St Peter's Basilica)、柬埔寨的吴哥窟、土耳其的苏丹艾哈迈德清真寺(Sultan Ahmed Mosque)。但是,是什么驱使着不同宗教信仰的人去参访本不是他们宗教圣地的宗教圣地呢?为了找到答案,美国亚利桑那州立大学(Arizona State University)的研究人员在2013年以蓝毗尼为例,调查人们来到佛陀降生地的缘由。

梵蒂冈圣彼得大教堂正在举行弥撒(图片来源:Alberto Pizzoli/AFP/Getty)

“我想知道不同信仰的人来到同一个地方的动机和体验。”亚利桑那州社区资源和开发学院(School of Community Resources and Development)副教授、项目首席研究员吉安·P·努帕尼(Gyan P Nyaupane)博士说。

研究报告称,接受调查的很多印度教徒和基督徒说,他们参观蓝毗尼是因为他们认为佛教跟他们自己的信仰很相似。比如,很多印度教徒认为佛陀是毗湿奴(Vishnu)的转世,所以他们也视蓝毗尼为圣地。而另一方面,很多基督徒认为佛教和他们的信仰没有冲突。

“佛教徒有着更高的宗教动因——比如,为了感觉更接近佛陀并进行祝祷——而非佛教徒则有更多的休闲、学习和社会动因。” 努帕尼解释道。

佛诞日的点灯仪式(图片来源:Paula Bronstein/Getty)

《遗产旅游杂志》(Journal of Heritage Tourism)2009年8月刊发表的一项研究也持相同观点。该文的结论是,游客前往圣地主要有4点原因:一是该地具有全球知名度(比如世界遗产);二是有经典的建筑(比如圣家堂(Sagrada Família));三是该地与名人或著名事件相关(比如圣保罗大教堂(St Paul’s Cathedral)与王室婚礼);最后是精神层面的原因,很多人在游览文化和宗教景点时能获得内心的平静。

就我来说,我来这里主要是因为对佛教寺庙发自内心的喜欢和热爱。当我走进一座寺庙,我内心感受到难以诉诸文字的平静与和谐。这可能是佛香的作用,也可能是因为平和的诵经声,抑或是因为我痴迷于寺庙博采众长的建筑风格。在印度,泰国和世界各地参观了无数佛教寺庙后,我想象佛祖诞生地之游应该会更有收获。

我参观了蓝毗尼的主建筑群,从摩耶夫人祠走了2.1公里,到达蓝毗尼博物馆,途中经过世界上很多国家因佛祖之名而在此建造的寺庙和舍利塔:有缅甸耀眼的金庙(Golden Temple),有泰国用白色大理石华丽装饰的皇家佛寺(Royal Thai Buddhist Monastery),有屋顶雕龙具有佛塔风格的越南Phat Quoc Tu寺,也有用鲜艳壁画讲述佛陀教诲的德国荷花舍利塔(Lotus Stupa),这些都让我叹为观止。

泰国的玉佛寺(图片来源:Tim Graham/Getty)

当我走到收藏着大量佛教工艺品和照片的博物馆时,我就像是巡游世界了一般,感受到佛教对这个星球和人类的深远影响。和到访世界其他的圣地一样,蓝毗尼之行让我增长了知识,增强了洞察力,并培养了更为宽广的胸怀。

毕竟,不论是脱下鞋履踏入佛殿,还是在走进清真寺前披上头巾,抑或是静静地坐在教堂里,感受与周围在座者心心相惜,这里面总有些不同的细微之处。

(责编:路西)

Where Buddha was born - By Susmita Baral

But none of these architectural gems hold the symbolic and historical value of Lumbini, a province at the foot of the Himalayan Mountains in the Terai plains of southern Nepal. One of four holy pilgrimage sites for the 488 million Buddhists worldwide, this region marks the birthplace of Buddha, who was born Prince Siddhartha Guatama in 623BC to King Suddhodhana and Queen Maya Devi.

A World Heritage Site since 1997, Lumbini has attracted travellers and worshippers for centuries. In 249BC, Indian Emperor Ashoka visited and left his tribute to Buddha: four stupas and a stone pillar with a figure of a horse on top. After a period of neglect, the site was rediscovered in 1896 by German archaeologist Alois Anton Führer and later recognised as Buddha’s birthplace based on the analysis of archaeological remains.

Today, more than 400,000 travellers visit the sacred site each year, wandering among the ruins of ancient monasteries and stupas. They walk clockwise around Ashoka's stupas and stone pillar to pay homage, and they explore the Maya Devi Temple, where it’s believed that the queen gave birth, bathing in a nearby pond beforehand. And every April or May, during the first full month of Vaisakh, the one-day Buddha Jayanti festival brings thousands to the region to commemorate Buddha’s birth, enlightenment and death through prayer and meditation.

In addition to being such an important pilgrimage site, Lumbini also attracts thousands of people of various backgrounds and denominations, much like St Peter's Basilica in Vatican City, Angkor Wat in Cambodia, and the Sultan Ahmed Mosque in Turkey. But what drives travellers to visit religious hubs from faiths that are not their own? To find out, researchers from Arizona State University (ASU) used Lumbini as a case study in 2013, surveying visitors throughout the year on their inspiration for visiting Buddha’s birthplace.

“I was interested in understanding the motivation and experience of people of different faiths visiting the same sites,” said lead researcher Dr Gyan P Nyaupane, associate professor at ASU’s School of Community Resources and Development.

According to the report, many of the Hindus and Christians that were surveyed said they visited Lumbini because they found Buddhism to be similar to their own respective faith. Many Hindus, for example, believe that Buddha is a reincarnation of Vishnu, and ergo accept Lumbini to be holy. A lot of Christians, on the other hand, see Buddhism to be non-conflicting with their faith.

“While Buddhists have higher religious motivations – such as, to feel close to Buddha and to pray – non-Buddhists have higher recreational, learning and social motivations,” Nyaupane explained.

Previous research published in the August 2009 issue of the Journal of Heritage Tourism agreed, concluding that travellers are drawn to sacred sites for four main reasons: they are world-renowned and globally branded (like World Heritage Sites); they feature exemplary architecture (such as the Sagrada Família); or they are associated with famous people or events (like St Paul’s Cathedral and the royal wedding). There’s also the spirituality component: many people find inner peace visiting cultural and religious destinations.

In my case, my visit was primarily driven by an innate love for Buddhist temples. No cocktail of words can exactly encompass the serenity and inexplicable feeling of harmony that I experience when entering one; perhaps it’s a product of the incense, the mild chanting or my fascination with the eclectic styles of Buddhist architecture. But after visiting countless Buddhist temples in India, Thailand and other parts of the world, I imagined a trip to Buddha’s birthplace would be even more comforting.

As I explored the main Lumbini compound and walked the 2.1km route from the Maya Devi Temple to the Lumbini Museum, I passed the numerous temples and stupas that have been erected by nations around the world in Buddha’s honour. I was left in awe, marvelling at Myanmar’s eye-catching Golden Temple, Thailand’s ornate white marble Royal Thai Buddhist Monastery, Vietnam’s pagoda-style Phat Quoc Tu Temple with dragons on the roof, and Germany’s Lotus Stupa with its colourful frescos of Buddha’s teachings.

By the time I reached the museum, which is filled with Buddhist artefacts and photographs, I’d felt as though I’d taken a walk around the world, experiencing the immense impact Buddhism has had on the planet and its people. Much like visits to other sacred sites around the world, the day had expanded my knowledge, broadened my awareness and allowed me to cultivate greater tolerance.

After all, there is just something different about removing your shoes before entering a temple, putting on a headscarf before entering a mosque, or sitting silently in a church that brings forth a feeling of solidarity with others around you.